Like I have said in an earlier post, I am a Hitchcock fan. I think he is a genius, but this movie made me think again about the magnitude of his genius. Truly, this man was light years ahead of his time with the way he put together the masterpiece of a psychological thriller, Psycho.

This movie opens with a couple in a hotel. Right off the bat there is a woman on full display in her underclothes. Now, this is not a stretch in movies today with completely scantily-clad women and full-on nudity, but for a film in 1960, I can imagine this might have turned quite a few heads. And this is just the start. Hitchcock pushes boundaries throughout this movie.

Said woman, Marion Crane is a secretary for a real estate company. That afternoon, after a clandestine meeting with her boyfriend, Sam Loomis, and when she returns to the office, a client drops off a large amount of money in cash. Marion seems cool enough about this huge sum of money when her boss tells her to deposit it into the bank right away because he feels nervous about having it around the office. Our lead lady, instead of going to the bank, decides she is going to steal the money to have a future with her indebted boyfriend. So begins a chain of events expertly captured by Hitchcock’s trained eye. The movie is titled Psycho, and this theme of the mind plays in right from the start with Marion role-playing scenarios replete with conversations spoken out by different players. Suspense is threaded into the very fabric of this movie in layers that keep you rooted to your seat (I didn’t move positions even once during the almost 2 hours!). Marion manages a treacherous journey to almost being with her boyfriend. However, a rainy night brings her to the Bates’ Motel. Here she spends a night, and that is where the psychosis kicks in. The owner of the hotel, Mr. Norman Bates, is not all he seems. And Marion might just be in a lot of danger.

Hitchcock marches right into the mind of a deranged killer. Dissociative Identity Disorder (previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder) is the premise of this movie, and while research around this area was being compiled, and various print and media were tackling this subject at the time, Hitchcock (in my mind) does the best work of portraying and analyzing the condition. Mr. Norman Bates has this condition. How does it play out?

Hitchcock’s angles, as always, are a cinematic technique to be studied, repeated and revered. He has the talent to create fear and anxiety and despair and utter suspense with the way he films his scenes. You get an overview shot of Mr. Norman Bates removing his mother from her room and carrying her downstairs to the cellar. Not too close, but just close enough to get you thinking about what this means and what will happen next. When Lila Crane goes looking for her sister, Marion, in the dark cellar, the shadows and the eye’s view with which she approaches the person she sees leave you immobile with fear. How does a director manage to achieve such a reaction in his viewers? Psychological thrillers these days don’t make you think as much! They don’t respect the intellect of their audience to put things together and create fear where those gaps are being filled. Hitchcock does that! He trusts that his audience is smart. He gives you just enough to create in your own imagination the diabolic scene that is unfolding in front of you, before it does! And then he adds a twist. Just when you thought you knew…

The motif of birds, these ones stuffed, is a recurring one in this movie, and sets the stage for Hitchcock’s later movie, The Birds (1963). Perhaps this was a horror theme he wanted to explore in more detail.

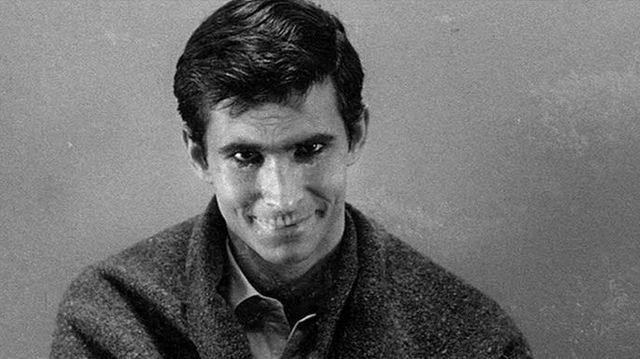

The actors are perfectly suited for their roles. Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates is the lanky and scared son who smiles inappropriately after something morbid is said. Janet Leigh as Marion Crane carries her heart and fear with sass and cleverness. She makes mistakes, but she is aware of them. Vera Miles as Lila Crane is picked for her likeness to Marion as a sister, but with just a bit more grit to make her probe the mystery and uncover the truth.

If you have a 2-hour window and are looking for a REAL psychological thriller, this would be it. Not one of those movies that delights in blood and gore to make you sick to your stomach. Not one of those that constantly has mangled figures hiding in the dark awaiting a “dumb” character’s entrance. No. This one is clever, and gives you as the viewer the satisfaction of putting the events together, before they are fully revealed, with your own cleverness.

So what say you, will you watch Psycho?

©booksnnooks.org All Rights Reserved